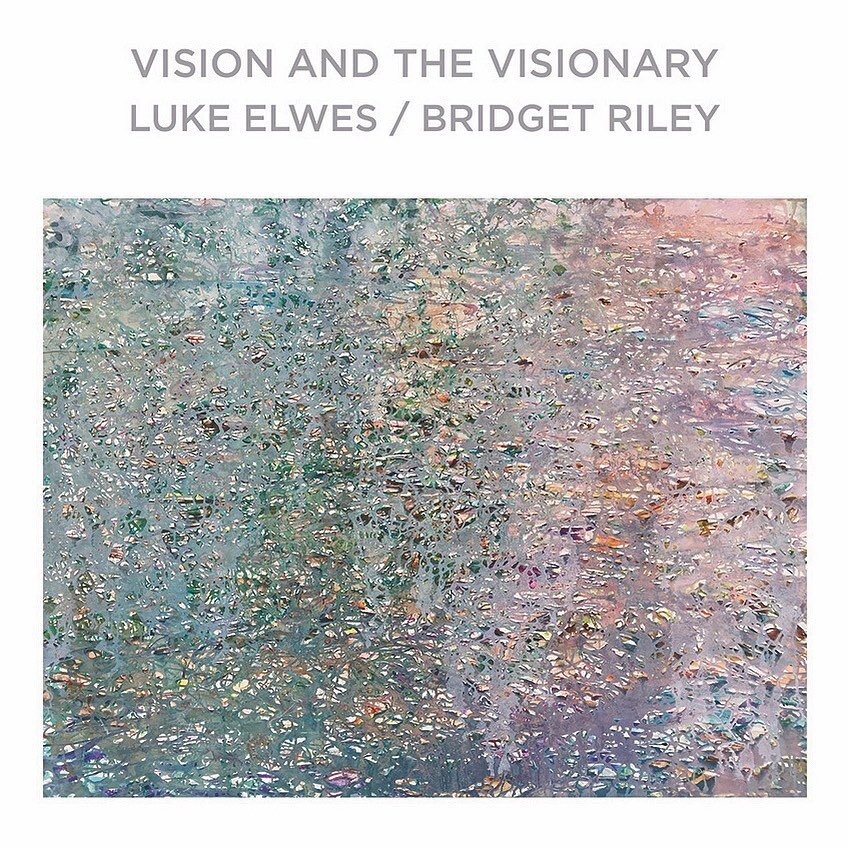

Floating world (2017)

/Over the last few years the work on paper (both those made here on the east coast and during residencies in America) as well as the ‘floating world’ paintings have begun not only to revolve around the aqueous realm but also grow into a wider meditation on natural forces. If they are reflections on landscape and memory, both many layered and recurring across time (and within which questions about how we might locate ourselves in the world have remained more or less constant), they are also fleeting commentaries – made through images uncertainly balanced between emergence & disappearance - on an increasingly unstable present.

It is as if the cumulative experience of travelling over many years to deserts, mountains and coastlines have been drawn together to form a locus around a time and space that is less culturally inflected (inscribed) and much more wildly elemental in its references to physical erasure, submersion and loss. The sense of discovery that still comes from exploring, walking or just ‘being’ in a place has also given rise to a feeling of reverie.

In particular the passage of days (marked out here with fugitive impressions on paper) spent by the tidal waters at Landermere in the interzonal territory of creeks and marshes on the East Anglian coast has developed into an extended reflection on dissolution and the return to wilderness (as witnessed also in the remote mountain tracts and extreme climates of Tibet and Mustang with their wind scoured walls and surfaces), a world that at one level appears cyclical and peaceful but at another is also fragile and endlessly mutating, where our tenuous hold on the material and historical record is constantly threatened and seemingly on the verge of destruction.

What has become more visible and urgent as a theme is connected, at least in part, to what the landscape writer Robert Macfarlane described in 2015 as ‘solastalgia’, a term he uses to encompass recent art that is, ‘unsurprisingly, obsessed with loss and disappearance’. ‘Solastalgia speaks of a modern uncanny, in which a familiar place is rendered unrecognisable by climate change or corporate action: the home becomes suddenly unhomely around its inhabitants’. We dwell in the knowledge – no less so in the Anthropocene – that everything returns to dust.

Luke Elwes February 2017

Note: Robert Macfarlane: ‘Generation Anthropocene: How humans have altered the planet for ever’, Guardian April 2016. And Amitav Ghosh deals with similar issues in ‘The Great Derangement’ (Berlin September 2016)