On a day when you are heading out to create a piece of work in the countryside, what's the process? What time do you set out? What equipment do you take? What are your painting clothes? What do you take to eat and drink?

It largely depends on the conditions on any given day and, if I’m by the water, on the nature of the tides. The decision about when and where to go is more instinctive than planned, and for me this is a deliberate part of the working process, to allow continually for the unexpected. The only constant is that the work will be made outside in the open and executed in one continuous sitting. Often this means working without a break for two or three hours at a time.

Sometimes I begin the day by walking along the water’s edge in Landermere or when the tide is out by retracing new or familiar routes across the meandering tracks over the tidal marshes. When the morning tide is rising I might row further out into the maze of creeks and inlets, to find some hidden corner of the backwaters. This could be soon after sunrise when the light is clear and the stillness is broken only by the sound of birds, or, on cold winter mornings, when the silent landscape is shrouded in a sea mist. Or it could be late afternoon, when the wind drops and vivid reflections play on the water’s surface, a time (often during the golden hour) when shadows throw the shapes of the land into relief or the low winter sun creates dark silhouettes in the silvery light. And occasionally I might continue on into the night, guided by the soft moonlight and working simply by feel and memory.

When I head out I carry only what is essential with me: a sheet of thick hand made paper taped onto a board and a shoulder bag with water and a box of materials, as well as some kind of waterproof and a plastic sheet, either for sitting on (where the ground is soft or wet) or for use as a makeshift windbreak, or for covering work in a sudden downpour. On colder days I use fingerless gloves to stop my hands freezing too quickly. At times, in an open boat or out on the marshes, I get very wet but that’s just part of the elemental engagement I’m looking for. In Vermont last year for example I would often set out for the day in snow boots and mountain jacket with a roll of paper and specially cut lengths of plywood tied with improvised rope handles that could be carried from place to place along the icy river banks.

Can you describe a typical day when you're working in this way? Again, what's the process?

There isn’t really a typical day, although at times I find myself concentrating on a particular patch of ground, a location that might be long familiar to me but which I want to revisit under new conditions as a way of extending the conversation between past and present, between what resides in memory and what emerges in the present moment.

Sometimes I work continuously over a period of days, rapidly making and remaking a series of smaller images, only some of which I will keep. At other times I will work on one large image from the beginning to the end of the day, recording the shifting weather and light as well as the constantly mutating shapes that rise and fall in the tidal waters. There is also a solitary oak tree by the water’s edge that I return to at different times of the year, continually recording its passage through the seasons from the spare intricacy of its winter outlines to the unfurling growth of spring and the dense verdancy of summer.

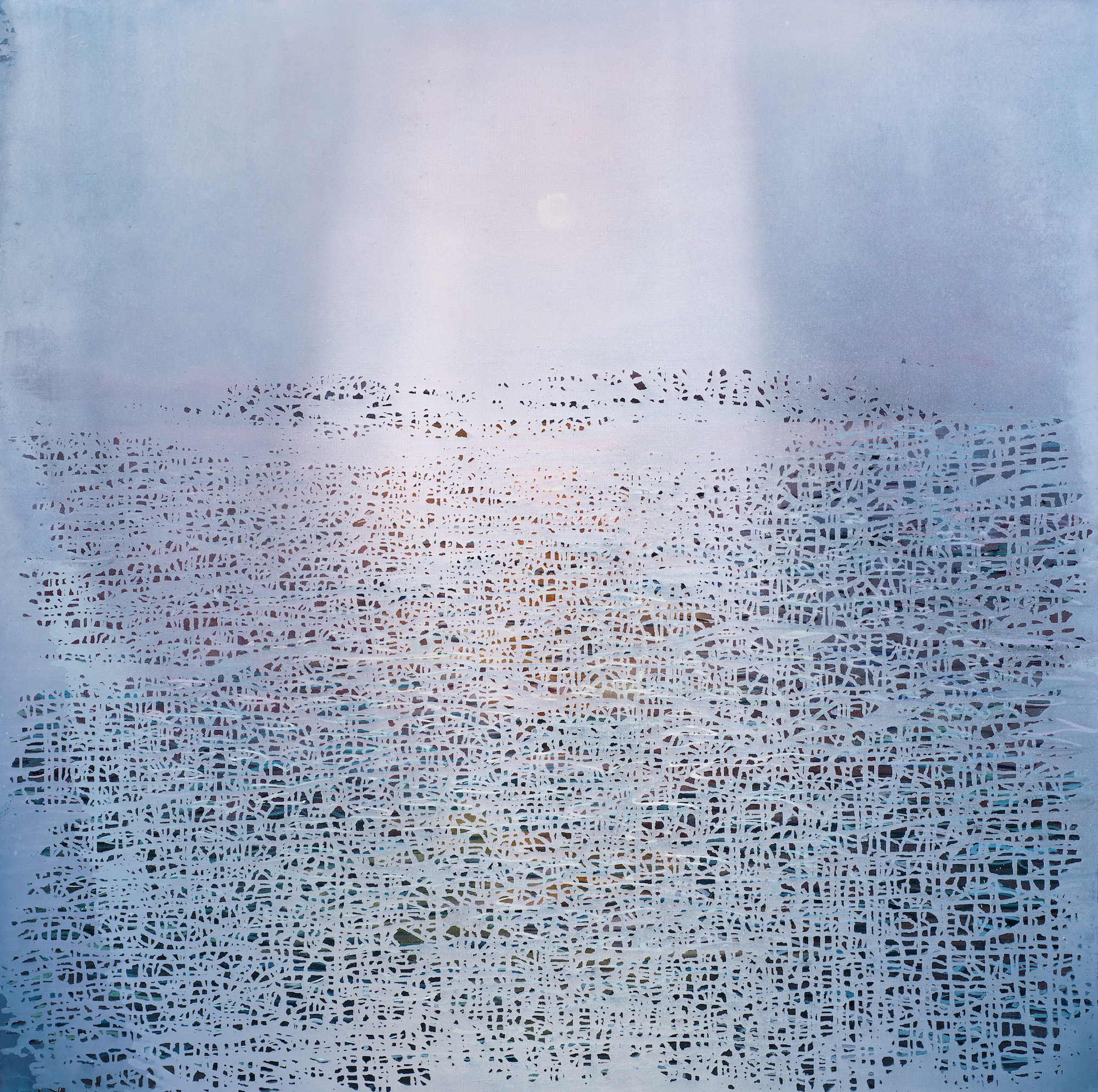

Often I will work on smaller pieces at an old wooden table that faces out onto the creek in front of the King’s Head in Landermere, or if it’s going to be a larger piece I’ll cut a two meter length of paper and fix it to an old wooden door that lies on the ground. The paper is then saturated in rain or river water before being marked and stained with pens, crayons, coloured ink and gouache. Often I combine these with mud or other organic matter found on site, and in order to keep the image fluid and malleable I will then allow the rising tide to wash over and even submerge the picture surface during the working process. In this way I can continue to work without pause for many hours, allowing the various pigments to float, drip and run over an absorbent surface, before they eventually begin to settle and dry on the paper. Often the result is surprising and unpredictable, with earlier markings resurfacing through transparent overlays or delicately mapped out areas fading away beneath opaque washes. Only when the image has completely dried out, which can take some days (particularly if the atmosphere is damp), can I then see how the assorted natural and man made elements have combined and whether I feel it has succeeded or failed as a picture.

What is it about East Anglian landscapes that attract you – and how do you decide on specific locations?

The specific locations are incidental, it’s more to do with their proximity to water. The estuarine and coastal landscapes of East Anglia often seem on the verge of dissolution, of melting away into an empty expanse of sea and sky. Beyond the tideline they have an unfixed quality, marginal and uncultivated - a wilderness of reflecting light and shifting patterns. Robert Macfarlane describes in his essay ‘Silt’ this soft bluish silvery haze that causes the elements to ‘blend and interfuse’, producing a ‘new country’ that is ‘neither earth nor sea’.

When I first saw the Blackwater estuary on a silent winter’s day fifteen years ago, the glistening expanse of mud and silt reminded me of the desert. One of the islands in this luminous tidal realm - Osea Island - seemed to float like a mirage on the horizon. Only accessible at low water via an old Roman causeway, it was otherwise completely cut off, a self contained parcel of space and time, and the sense I had that day (and the many that followed over a seven year period) of being alternately connected and isolated was very appealing. The place moved to its own rhythm, a vessel of ancient history whose fragile lineaments were constantly being broken up and recomposed by the surrounding waters.

I stayed on the island for periods throughout the year, recording on paper its ever-changing liminal quality while enjoying (in contrast to the extended journeys across unfamiliar terrain which have often informed my painting process) the sense of sitting in one place and watching nature’s myriad forms pass me by. And beneath the surface, there was the constant pull of the past, of glimpsing in the mud and creeks fragments of the island’s history - old tracks, boat carcasses, shell banks and oyster beds - as well as those transient signs of more recent use, the remnants of a Victorian pier and empty concrete bunkers.

The layers of the past buried in the soft ground of the East Anglian coast have entered literature and my reading of Great Expectations as well as W.G.Sebald’s Rings of Saturn and Roger Deakin’s essays have also played a part in my work. About eight years ago, when we left the island and moved further north along the Essex coastline to a location at the end of a rutted farm track that now sits precariously on the edge of Landermere creek in the Walton backwaters, I was fascinated to discover that Arthur Ransom had based his book Secret Water on the surrounding maze of islands, channels and inlets. Paul Gallico’s The Snow Goose was also filmed here.

There is in these low lying landscapes a hidden quality, places of silence and occasional abandonment, where nature rises and falls, where things appear and disappear in the cycle of tides, and the passage of other lives drift to the sound of birds and waves – an often floating world where the mind slows down and reflects.

How does the weather on the day affect, influence and guide the creative process. Have there been any extreme examples of this? When and where were they?

The elements are an essential part of it, and with the work on paper done here in East Anglia it is the weather’s unpredictability that guides the process, preventing the easy repetition of familiar motifs or any certain knowledge of the outcome. I can begin working on a clear day and suddenly what I’m seeing vanishes into a fog or rolling storm clouds. The shapes I’m drawing start to merge and dissolve while rain spatters and dapples the coloured surface, and sometimes washes it away entirely. In wintertime the north easterly winds can make it hard to work at all, while on a dry summer’s day I often have to work much faster, before the crayons I’m using become too soft or the pigments too dry, leaving the paper’s surface frustratingly static and unresponsive. But there have also been times when I’ve felt I’m wrestling with rather than responding to the weather. Making watercolour drawings in the dawn light on the Tibetan plateau was complicated by the water turning into ice on my brush, a problem I also encountered in Vermont when trying to wash the surface of a large picture in a mountain stream and then watching as icy particles formed all over it. In these extreme environments, snow can also fall rapidly, carpeting the ground where I’m working, and when it melts, as it did later on in the month I spent by the Gihon river, the snow and ice floods the landscape and tears away trees and vegetation from the banks. At the other extreme I’ve worked in arid desert locations where I’ve had to be very sparing with the water I ‘m carrying so there’s enough left to drink as well as to mix paints. And when it finally ran out on one occasion I had to fall back on a can of coke to finish the picture.

It seems like there is a complex, symbiotic, relationship of creativity within the process, where nature is shaping the work as much as you are 'shaping' nature by fixing it, however loosely, on paper/canvas. Is that right? Could you elucidate on that at all?

Yes, I think that’s a good way of putting it. Explaining this relationship in another article I said that ‘the final image belongs as much to the elements as the artist who began it’. This applies particularly to the work on paper but relates equally to my paintings which although much longer in gestation are also a record of process and time. Some years ago I did a series of paintings based on a journey to the Himalayas where I wanted to represent the way the natural minerals and pigments, found locally in the earth and rocks, are used to paint man made surfaces with vibrant symbolic colours and how, through the corrosive action of wind and water, they eventually dissolve back into the ground. Andrew Lambirth said of these works at the time: ‘everything is reduced to dust eventually by the elements, but in the meantime we may enjoy the trace of their being’.

If the paintings are a meditation on this process, often done from memory in the studio, the work on paper has a more immediate and visceral relationship to the natural world; they are both about, and shaped by, the place where they’re made. Perhaps this is best elucidated if I describe the way the process might begin: by registering marks, things that catch the eye - a passing bird, a blossom, a cloud, tracks in the mud, bits of flora and fauna. An accumulation of phenomena, both distant and close at hand, that creates a kind of equivalence, a response on a particular day to a place. It appears familiar but remains strange, a mutable scene that is never quite the same as the days blur and seasons shift, where streams alter their course, swelling and diminishing over time, and where mud flats that were previously sparkling black and silver are now softly carpeted in pale grass and wild flowers. What forms is a series of recorded moments, a diary of days composed of sequential memories (recalling the last time I was here) and sensory stimuli of the most immediate and fragile kind. It is a way of proceeding that is openly receptive, avoiding correction or revision while keeping the elements continually in play. The materials I use dictate this process, so a picture of the water is made with the water, the scattered marks and colours running in a way that directly mirrors the tidal flow that surrounds it or the rain that sweeps over it. The writer Robert Macfarlane put it this way in a letter he sent a while ago:

‘I might try to articulate what I find so unusual and compelling about the work: its localism, for a start. But also the hover between encryption and archetype (enigma and fabulous openness). As you hold on to a leaf, a shell, feather or pebble before returning it to its microcosmos, you learn to see not the names of things but the things themselves. Absolutely. We are both collectors, but not in the possessive sense of that word; quite the opposite. Surrenderers of sorts.’ NB. Robert Macfarlane is the author of The Wild Places (Granta, 2008) and The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot (Penguin 2012)

A sense of place feels like a starting point, but perhaps not an end point, for your work. If they are landscapes, or maps, then they would seem to record internal worlds as much as topographical ones. Similarly, they could be seen as recording time, duration – as much as place. Of course, time and duration are needed if we are dealing with concepts of flux, transience etc. Is this part of what you are exploring?

A sense of place is the essential starting point, as is the experience of journeying through it, responding as Richard Long described it, ‘to the earth moving beneath your feet’. But the work is also about memory and time as much as what is seen – the memory of what was once there, as well as the memory of previous work done in same place. The paintings become a way of examining my own transient presence as well as the changing nature of the landscape itself. By way of example, when walking along a mountain trail you can see the path travelled yesterday stretching behind you and the day to come running ahead of you. In this sense time and space become synonymous.

The pictures record not only those ephemeral moments of personal submersion but also chart a deeper history, tracing out those often barely discernible fragments and stories (whose signs are often lost or barely discernible) that make up a place, the invisible yet palpable layers which lie within and beneath the surface. The rushing mountain stream I worked beside for a month in Vermont for example, was called the ‘Gihon’ (named after one of the four mythical rivers of Eden) and seemed to contain within its flow the quiet language of the past.As with my earlier desert paintings they combine the mapping out in space, on paper and canvas, of a physical journey with a kind of cultural excavation that speaks of duration, time passing. This experience was especially acute in Vermont where I set out to create a visual diary by making one picture a day in one place over the course of a month as winter turned to spring. Despite these differing approaches and locations there is in all the work a sense of the present erasing the past, something physically manifest in the shadow lines left in the residue of coloured ink or the evidence of earlier drawings occasionally glimpsed through subsequent layers of paint. For the critic Nicholas Usherwood, writing about the work in 2009, it speaks of ‘a continuous process of loss and recovery’.

Finally – and quite a vague and encompassing question: can you give me some thoughts on the use of abstraction in landscape painting?

I find both ‘abstract’ and ‘landscape’ somewhat limiting terms - I’m more interested in working at the edge, or on the margins of both. There is always a fixed starting point in time and place, a relation to the exterior world of phenomena that allows for a dialogue with an interior space of recollection and feeling, but this is less to do with ‘taking in’ a landscape as the idea of ‘landscape’ itself and what this means in relation to other times and cultures. Early on I was fascinated by the desert paintings of aboriginal Australians, images that were read at the time by a western audience as abstract patterns but which in fact directly recounted their experience of walking over ancestral ground. They did not paint the horizon because they could not touch it. My aim likewise is to be as receptive to the surface of the visual field I’m moving across as what lies unseen beneath it. The paintings grow out of particular encounters with places both distant and near, and the subsequent marks deployed on canvas and paper can be read as hieroglyphic texts - or even as maps of the ‘geographical unconscious’ – that set out to evoke both the trail of our presence and the passage of time. They place, as Odilon Redon once put it, ‘the logic of the visible in the service of the invisible’. (‘La logique du visible au service de l’invisible’.)