Luke Elwes: Psychological Geodesist

As a boy I used to look of maps, / was … obsessed with maps, the white areas most of all. They denote those places of which we know nothing, dark spots in the universe that exert a… savage attraction. That is why / went to sea. / had to visit those places. So one travels and travels, through Asia, through South America, up the river Congo, and it is… it is … a journey into one’s self, the drawing up of a vast mop. One becomes a …psychological geodesist. Journey into a Dark Heart by Peter Hoeg

Geodesy is earth measurement on a large scale, or surveying with allowance for the earth’s curvature. It seems to me that this is what Luke Elwes does – in both literal terms, and in a more personal, metaphorical but generally accessible way. His principal subject is landscape and our relationship with it, our journey through it, our response to it. Elwes has spent much of his painting career exploring alternative ways of looking at the world, and of how to depict the experience of being in it. Man within the universe, rather than controller of it. His new paintings are meditative and calm, conjuring an arena of dreamy speculation: they proffer the refuge of silence in a cluttered, hectic world.

Luke Elwes spent his earliest years in Tehran and grew up in the luminous spaces and under the big skies of Persia. Later, living in Britain, when he came to paint landscape it was a natural progression to move from the softness of Connemara and Wessex to the greater aridity of Spain, before he succumbed to the lure of the desert. (“The desert is the purest landscape, where the soul breathes; the place where we first came to touch the surface, and sense the forces moving beneath it.” Elwes 1991 .) His Australian paintings were fed by the example of the Aboriginal desert artists, by the writings of Bruce Chatwin, and by an awareness of two modern painters – Fred Williams and Alan Davie. But this group of pictures nevertheless remains an individual and remarkable contemporary response to journeying in the wilderness. Elwes confronted himself as much as the unfamiliar landscape, and recorded their dynamic interaction.

Why the desert? Not just for its purity, though very great is the need to escape the trappings of civilisation in order to think. Humanity has hardly left a mark on the shifting sands of the Sahara, yet nature is still very much in evidence. At night, or after rainfall, a whole host of plants and animals appear as if by magic. Beneath the apparently dead surface of the sand, the pulse of life continues unabated. All is there in potential. And it’s a refreshing alternative to the man-dominated environment. Elwes has wandered through the dry tablelands of New Mexico observing the Hopi Indians, he has visited the Chalbi desert and the Great Rift Valley in East Africa, which was probably the first landscape to register on human eyes. In his desire to see the world and our relationship with it afresh, Elwes is drawn ineluctably to first things and to last things – to the elemental.

What luck then to be invited at the end of 1996 to join an expedition to Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar on the high Tibetan plateau. This is one of the world’s most sacred places, and, like Delphi, is thought to be the centre of the world, its omphalos, or navel. Mount Kailash is identified in Hindu and Buddhist cosmology as the World Pillar and the Pathway to the Stars. The mountain is also identified as the abode of Shiva, from whose hair the life-giving waters of the Ganges descend to earth. Meanwhile Lake Manasarovar, known to the Buddhists as the “green-gemmed mandala”, is believed to have sprung from the mind of the Brahma. A sacred site, inaccessible and isolated, but the focus of concerted pilgrimage; such is the potency of the place that to walk a single circuit of the mountain is said to be sufficient to erase the sins of a lifetime. The circular route is a month’s pilgrimage. Elwes speaks of the redemptive powers of the magic mountain. It is a 50 kilometre walk around the base (only Buddha ever went up the mountain itself), and not everyone who undertakes it can complete the course. Material offerings, or ex votos, are scattered over the foothills and blown about, making it look a little like a rubbish dump. (The profane has its place in the scheme of things.) The way is strewn with carved and inscribed stones to mark the passage of previous pilgrims. To Elwes, sensitive as he is to the genius loci or spirit of place, it was like being on the roof of the world, with the sky close enough to touch.

Elwes took the unusual experience of the pilgrimage as a spur to his previous ideas, as a way of deepening his own enquiry. The mountain itself doesn’t feature in this series of new pictures. True there’s a small study of an idealised mountain shape, but aside from that, it is an unseen though pervasive presence. The holy river valley is on the other hand a favourite motif. The river’s source is at the base of Mount Kailash, and its flood forms a beautiful turquoise thread of water down the valley. Elwes, for the sake of pictorial and spiritual simplicity, in Fall, reduces the river to a ribbon of blue, intermittent on the canvas. This resembles the cut-outs or arabesques of Matisse, but also the prayer flags or paper prayers drifting on the wind around the holy mountain. As Matissean marks it exists as a flat pattern floating on the surface of the canvas. As a depiction, however schematised, of the descent of a river, it works within the picture space. The strength of it is that it can and does have both functions.

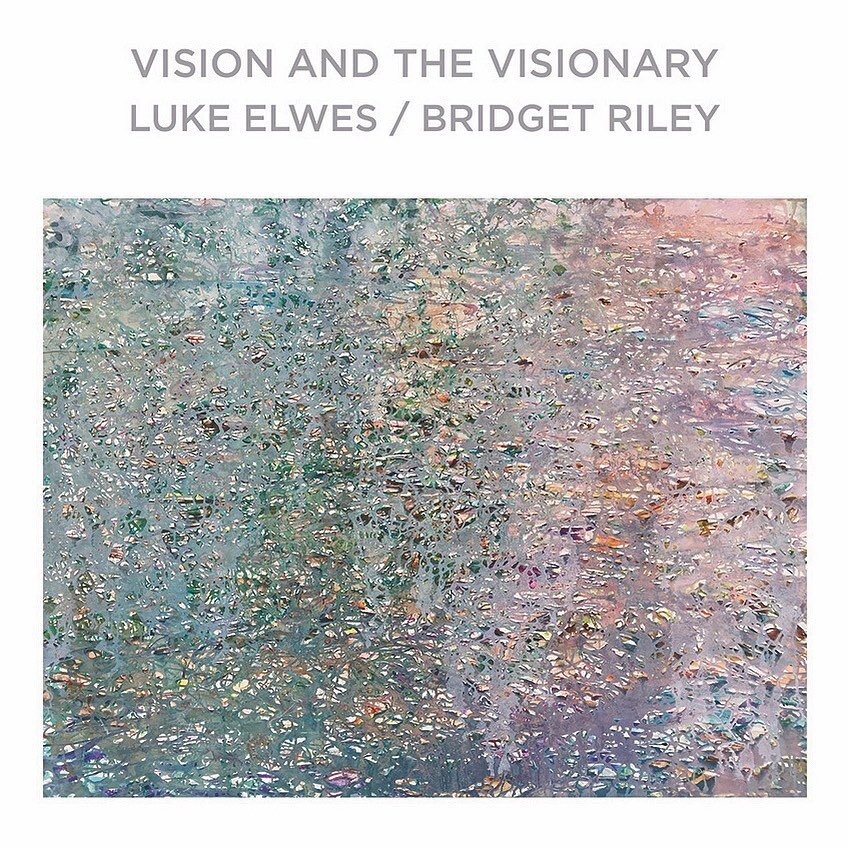

On the trek, Elwes made colour notations and naturalistic sketches in watercolour, as well as taking photographs. Back in his North London studio he picked up the traces of his previous work and sought to incorporate his newly-garnered information. Again, external influences played their part in the generation of new images. Elwes had been looking at the great waterfalls in Hiroshige’s prints, and the economic way the Japanese artist captures the sheer drop of water. (Interestingly, it appears often like a column.) Once again, simple shapes. Elwes had already begun to experiment with layered surfaces fractured like fretwork, the patina crisply broken-up into tiny windows, here and there revealing hidden depths excavated. He began to take this technique further. He might commence by scribbling across the surface of the canvas, making marks almost like automatic writing. Various layers of underpainting and undermarking would then be covered up by a thin wash of paint. This again might be partly removed by running turps over the new surface. It’s difficult to predict quite what will happen when another wash is flooded over the canvas, or even trickled on. The possibility of losing the surface altogether, clogging up the tooth of the canvas, simply by running too many washes over it, is an essential part of the process – it’s the yeast of risk. In these new paintings, Elwes achieves thinner surfaces than before and yet more complex layering; despite the aleatory nature of this part of his practice, he has grown increasingly adept in its manipulation.

Chords and echoes sound through the work as a whole. Certain themes recur. In 1992, Elwes, an acute commentator and historian of his own work, wrote: ‘In these paintings, two images have emerged, the meandering line and the divided surface. The lines are the paths of our own life, and the meandering course of all life, of branches, trees, roots and riverbeds. In their uninterrupted movement lies the search for markers, the signposts we need if we are to draw our own maps.” To take a specific example, the 1992 painting entitled Source displays profound kinship to Skin of five years later. There is a recognisable continuity of interests, combined with unflagging technical exploration. The group of paintings which feature a globe (see Arc, Navel, Roof and Breath) take a longer perspective on the same issues. Whether they refer to molecular, bodily or global structure, their analytical/emotional thrust is constant. The surfaces are even further worked, densely explored but not fussily. If we decide to interpret the image as a map, the scatterings of fields and dwellings should also be read simply as mark-making. The pictures are just as much about abstract ideas: divisions, boundaries, the edges of things. One of the key aspects of this group is a balance of power played out between light and dark. The arc of darkness encroaches on the lighted world, or the fruitful belly of the earth squashes night into a corner.

Elwes likes to keep his references multiple. He told me, for example, that Aboriginal desert paintings are also family trees. This is an important back-echo to the work, a formative influence. Likewise, there is the medieval belief that the earth was flat, that you could fall over the edge of it, and that the celestial canopy which was the sky, was held up on poles at its four corners. The stars were the holes in the canopy. For Elwes’ pictures, this is an important point of reference. Again, look to the maps made long ago, with their assumptions of knowledge and their admissions of ignorance. Perhaps with their inventions and blank areas (terra incognita) they were more humanly truthful than anything we can attempt today with our far superior technological resources. (We who can’t see the wood for the trees.)

These 4 foot by 8 foot canvases are the largest that Elwes has worked on. The double square format provides an appropriate horizontal spread for the journey and its alternative routes, though the first of the group, Navel is in fact vertical. A friend looked at it and said that it reminded her of what it felt like to be pregnant. Interestingly, Elwes is not only mapping space, but also the passage of time. The map-points and references have various layers of meaning. At sporadic intervals in the net of veining, branching lines (everything is connected) a cross appears. Is this a kind of hallmark or stamp of approval? (A sign of spiritual weight?) Crosses also simply mark unspecified points of importance on the map. Yet at every crossroads there is choice, and the possibility of new spiritual horizons. This is important. These are paintings which are both map or aerial view, and yet also suggest a horizon line. Now the focus has pulled out, and we see the earth from afar, as if from a satellite in space, yet the detailing is often distinct. Near and far are reconciled. The map floats in and out of focus at the margins, and then comes into clarity at the centre, just as the eye sees. The blue all-seeing metaphoric eye of the holy lake in Skin appears to be both navel and nipple, the circular journey around it tracing the aureola. The pinky-ochre desert of Tibet seems very like the actual derma (in animal terms) of the earth. In the same way rocks can become flesh.

Elwes is attempting to deal with the unseen. As from any patterning, however random (even damp stains on a wall), figurative images will emerge, so here and there a profile face materialises from the map lines. There are many fine shades to meaning, and a range of truths not immediately perceptible. Many fine shades to meaning, and a range of truths not immediately perceptible. Meditation on the pure yet ambiguous forms of Elwes’ paintings may reveal more. (Remark the benignant smile of Strand.) As Redon put it: “The logic of the visible in the service of the invisible.” These paintings also have the character of a palimpsest – an ancient document, that has had many stories written over it, some of which are partially erased, and others more legible. In the simple yet complex new paintings of Luke Elwes lie both stimulus and refreshment for the soul.

Andrew Lambirth (catalogue text for Pilgrim, Art First 1998)