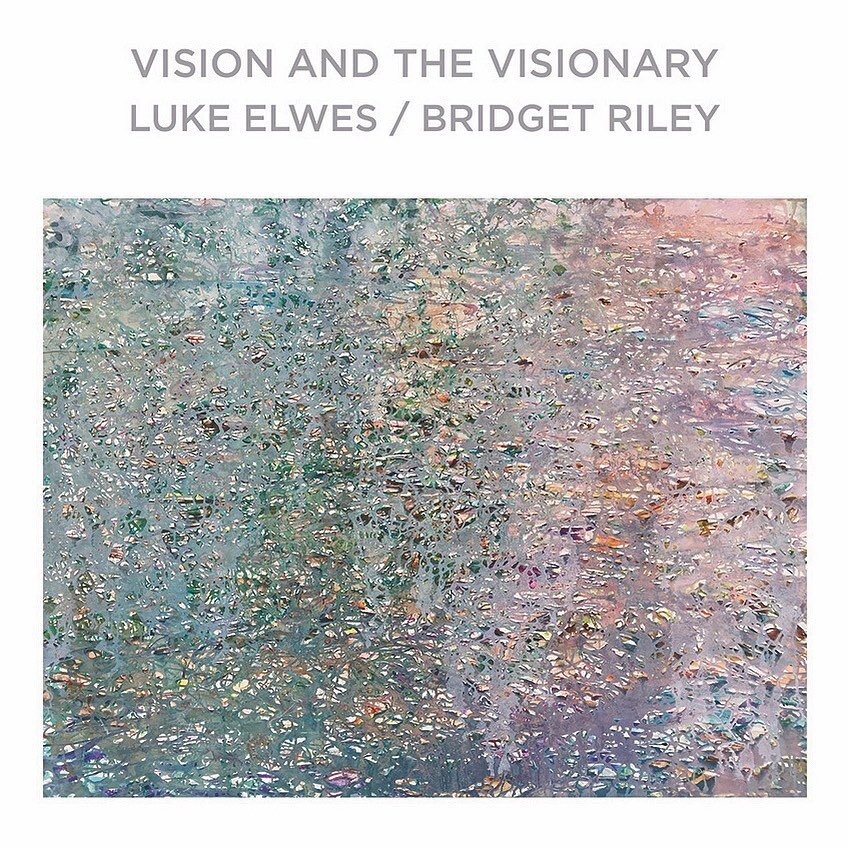

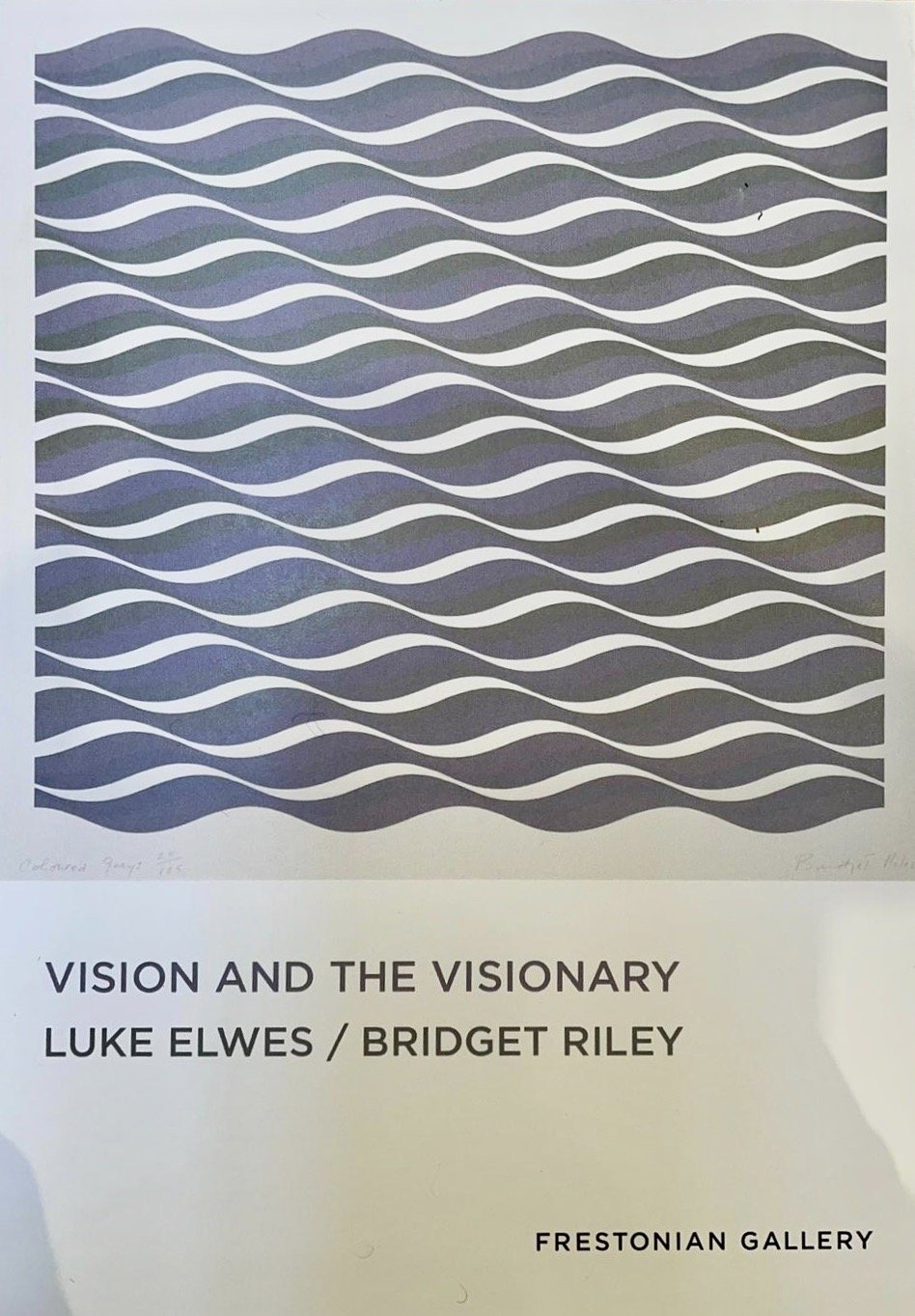

Between heaven and earth

/Sometimes a picture conceived in one context assumes an unexpected meaning in another, as when an author finds his own particular imagery reflected in the painted surface.

‘ Come with me,’ says the old man at last. He helps Kit to his feet and leads him to the other parapet, where he points far upstream. ‘Look over there.’

Kit follows the line of his arm and sees that the river below them emerges from a delta where seven other rivers have come together. They could, he thinks, be described as lesser rivers; yet each is so mighty in its own right that the word is inappropriate. They seem at once to flow down from the sky and break from beneath the earth, rushing vigorously, glinting in the sun..

‘These are the rivers,’ says Kit’s great-grandfather, ‘that flow between heaven and earth, and between earth and heaven.’

‘Where do they begin?’ Kit asks.

‘They begin at the fountain of life, and they end in the ocean of eternity; but the fountain is never exhausted, and the ocean is never full. And when they reach that delta, they mingle with each other and with springs you cannot see to form the river of life, encompassing everything men know and imagine and what they have yet to imagine. In its waters are mingled past and present and future, actuality and possibility.’

Extract from Anthony Gardner's new book 'The Rivers of Heaven', published this month. Find on Amazon