As Bridport Open Studios approaches, Alex Lowery’s paintings explore the Chesil Beach. From West Bay to Portland, his pictures offer a new way of looking at this coastline. Again and again visitors tell us how they have gone out after seeing the exhibition and noticed colours and viewpoints they have never seen before. I do it myself and feel very lucky not only to be with the paintings all day but then to go out into the landscape that inspires them and see it with his eyes. This extraordinary summer has been the perfect setting for Alex’s infinite seas and skies and the heady turquoise in the smoky soda-fired surfaces of Jack Doherty’s elemental porcelain vessels.

On 22 September we are moving from light to water as the theme (although light is crucial in this too). The new show, entitled Currents, brings together four painters who look at water in different ways. For Janette Kerr, water is deeply dynamic, whipped up the by wind and portrayed in energetic expressionist brush strokes. Vanessa Gardiner’s water is often a well of opaque colour, with geometrically divided areas of froth and shadow. Her blues sing out in rich notes calling to us. It’s a pleasure to watch people respond. Julian Bailey’s joyous seas seem to sparkle and move with thick impasto paint and quick gestural brush strokes. Luke Elwes turns the surface of water into a shimmering meditation.

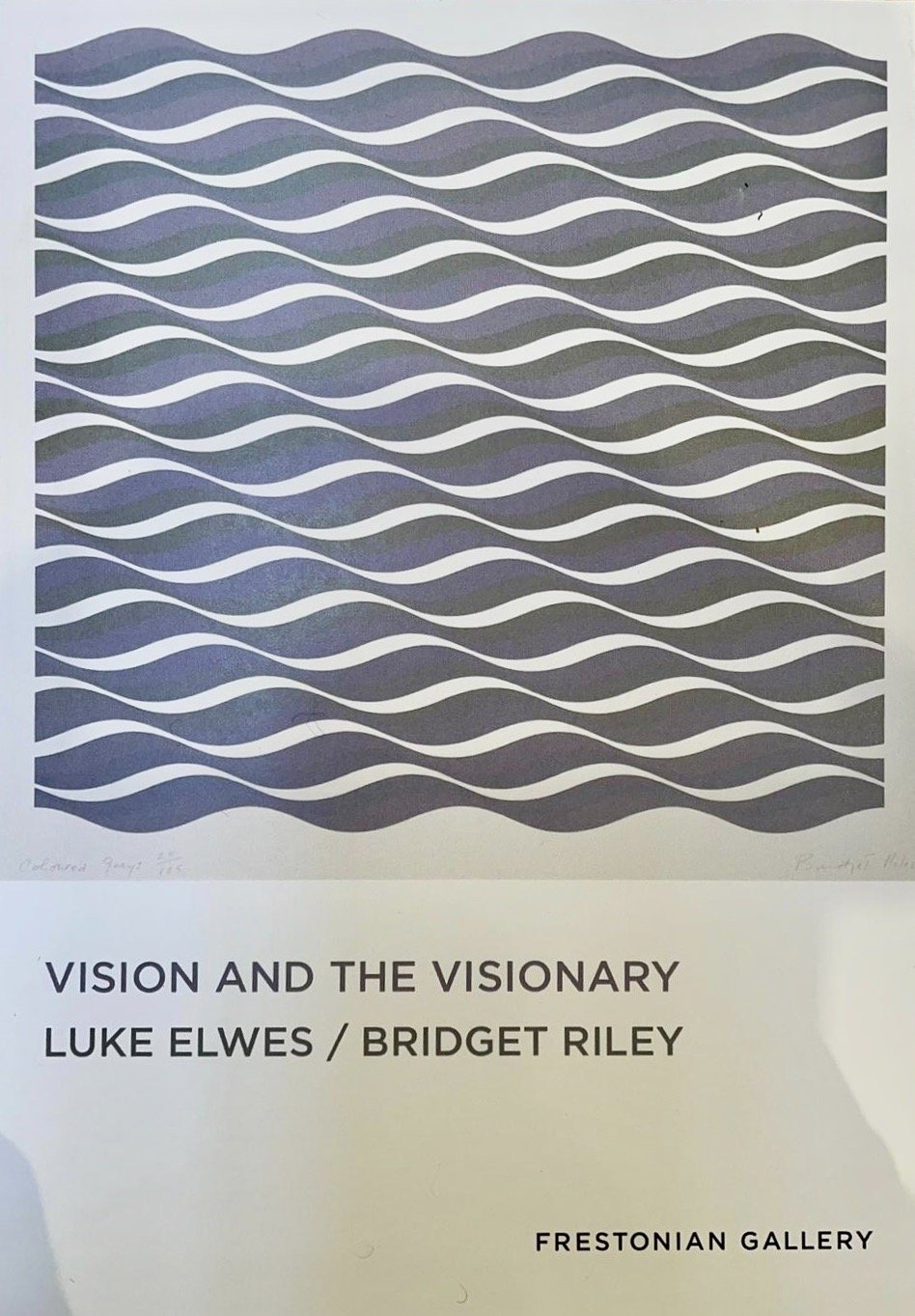

Luke Elwes came to this gallery through Alex Lowery. The two have shown together numerous times over the years, at the Estorick Collection in London, here at Sladers and most recently in Bergamo, Italy. Both artists make ambitious work in subtle, understated intelligent ways. As well as paintings Luke writes and talks about art in the Royal Academy Magazine, Galleries Magazine, on BBC Radio 4 and abstractcritical.com.

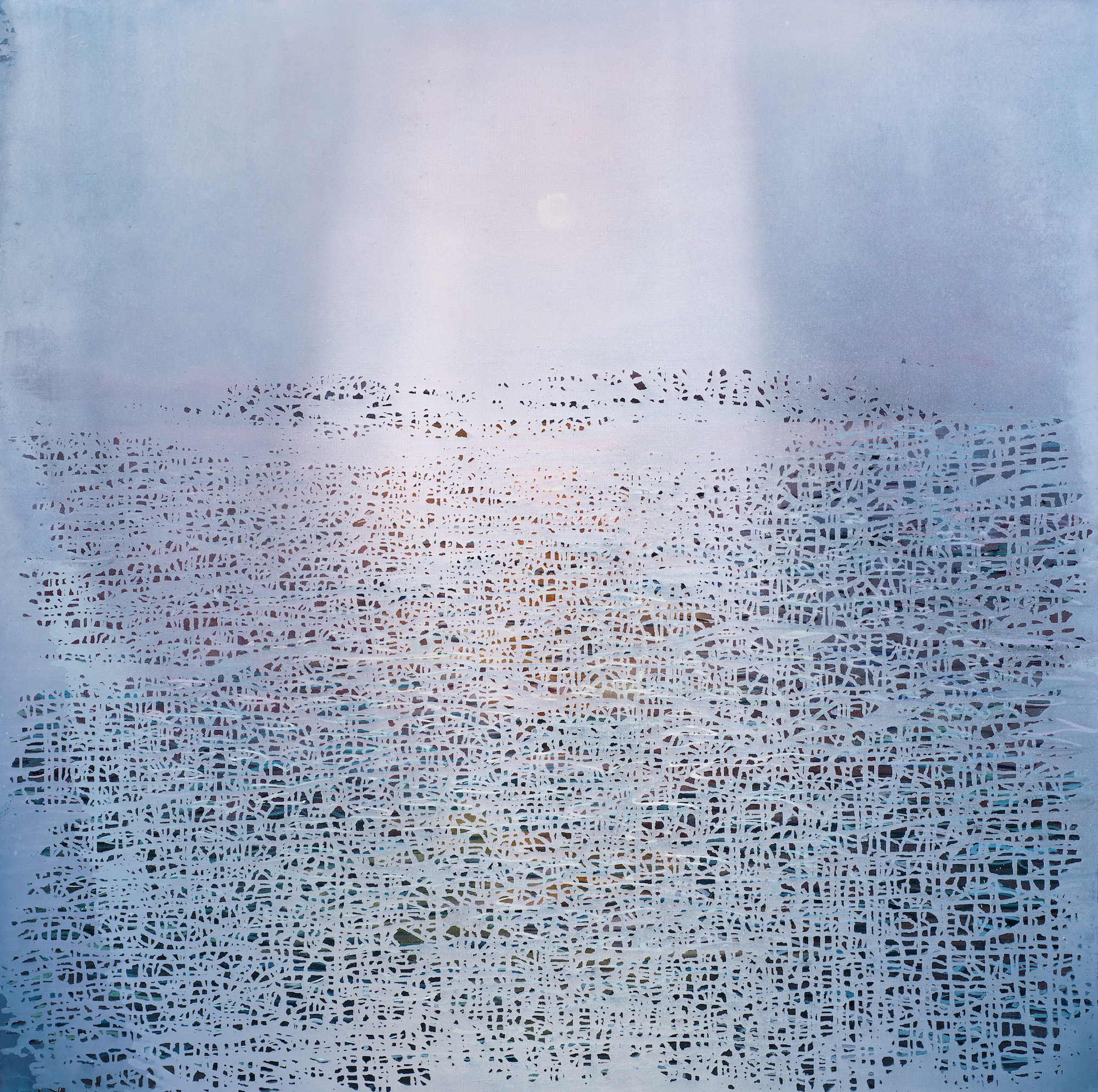

Luke Elwes’ own paintings involve layers of painting – areas of rich colour interspersed with white – which are dissolved and floated sometimes with river water or oil paint thinners and allowed to trickle or flow across the paper or canvas. The results seem to reflect light and invite the viewer to look into them as if they were pools of water.

‘For me,’ Luke has written, ‘it has become a way of marking my own transient presence in the flow of phenomena, of paying quiet attention to the shifting patterns on the water, the fall of light on a given day, and the incidental life that passes across one’s visual field. Beneath all this, there is also the delicate registering of material erasures, the disappearances and the brief resurgences, the momentary recollection of this place’s silent (sinking) past.’

Luke’s early years were spent in Iran, where the light and space of the desert were a formative influence. He studied History at Bristol University and Painting at Camberwell Art School between 1979 and 1985, and Art History at Birkbeck College, London University, becoming an MA in 2007. While working at Christies, he began to travel and write and in 1987 met Bruce Chatwin who inspired a trip to Australia. Since then he has continued to travel extensively, discovering and revisiting remote locations in India, Asia Minor and North Africa. In 1998 he was artist in residence on an expedition to Mount Kailash, a holy mountain in western Tibet. Since 2000 he has worked for long periods on an island off the East Coast of the UK. In 2013 he was awarded a grant to study at the Vermont Studio Center and in 2015 he was resident artist at the Albers Foundation (USA).

The idea of the journey is central to his painting, both its physical and temporal unfolding and its recollection in memory. Rooted in the particular, the images also explore an interior space.‘The future is not knowable country,’ he has written. ‘Out on the Essex marshes where I work, everything changes. It becomes an untended wilderness of dissolving paths and silted up streams where creeks and channels endlessly mutate in the tidal salt waters. Beyond the fragmentary system of sea walls and dykes one encounters an un-tethered world, prone to flooding and now bearing silent witness to the cumulative effects on this fragile ecosystem of climate change.’

Since the beginning of this year, Luke has been working on a series of paintings based on the experience of travelling by boat along a stretch of the river Ganges. The Ganga paintings draw on the power of this sacred river that flows through the precarious lives of the people and cultures that have thrived throughout history on its banks. His method of working, of gentle mark making, dissolving and erasing gives rise to a mood of reverie. Like watching water, nothing is permanent. ‘Perhaps the only response,’ Luke says, ‘(as one who paints) is to “gather in” the present and recognise that if the current is one of flux and uncertainty it is nevertheless still – in the earth beneath our feet, the ‘weather’ and the sky above - an essential realm of connectedness and embodied experience.’

Currents: new paintings by Julian Bailey, Luke Elwes, Vanessa Gardiner and Janette Kerr RSA Hon is at Sladers Yard, West Bay from 22 September until 11 November 2018.

www.sladersyard.co.uk