Luke Elwes | Constellation | Frestonian Gallery 2024

/Luke Elwes: Constellation by Andrew Lambirth

Luke Elwes is a painter intimately engaged with landscape and memory. He is a passionate traveller who responds to the world around him by making another parallel journey: to the inner passes of the self.

Elwes spent the month of September 2022 in north Mayo, facing the Atlantic Ocean on the western edge of Ireland, having been awarded a fellowship by the Ballinglen Arts Foundation. He was given a cottage and a studio, which he didn’t much use as he continued his practice of working outdoors on large sheets of paper in all weathers. He usually works outside in the Essex marshes, at the former studio of Eduardo Paolozzi and Nigel Henderson at Landermere Quay. He has been going back there regularly for the last 16 years, and has grown exceptionally receptive to the slightest change of tide and light. Inevitably, the place has become ‘a sort of fixed point’ in his life and work. As a result, he is used to marginal places, landscapes on the edge.

When he was younger Elwes visited parts of Ireland, Connemara for instance, so his Mayo sojourn was not exactly the discovery of a new place so much as the recovery of familiar territory. The area is suffused with history: Céide Fields, one of the earliest and most extensive neolithic field-systems in the world, is just a few miles from Ballycastle where he was based. The terrain is dominated by the Nephin mountain range, a name that translates as ‘Heavenly Sanctuary’ or ‘Finn’s Heaven’. (Finn MacCool being the legendary warrior hero who built the Giant’s Causeway.) Nephin is the highest stand-alone mountain in Ireland, and the name is perhaps related to nemeton, a sacred space in ancient Celtic religion, often found within a sacred grove.

As the references gather, one is reminded of past expeditions Elwes made, to Mount Kailash on the high Tibetan plateau in 1996, and to the ‘Hidden Kingdom’ of Mustang in 2008. Kailash in Hindu and Buddhist cosmology is the ‘World Pillar’ and the ‘Pathway to the Stars’, and Mustang is a corruption of the Tibetan word ‘Manthang', meaning ‘Plain of Aspiration’. Every new experience is informed by what we carry within us of the past, and likewise each painting Elwes makes draws upon a potent fund of memories and acquired knowledge. In this way, his paintings of Ireland also contain elements of other places, other experiences, as well as benefitting from the practical painting lore he has learnt over the years.

County Mayo offers a landscape of greys and greens, varied with the white of sand and the black of rock or peat stacks. The sea is one range of greens, the bog another. Blue surprises with its power in this aqueous atmosphere. The German writer and Nobel laureate Heinrich Böll came to Mayo in 1954, later writing about it in his Irish Journal. Nothing fundamental has changed: ‘The sea was pale green, up front where it rolled onto the land, dark blue out towards the centre of the bay, and a narrow, sparkling white frill was visible where the sea broke on the island.’ And: ‘Azure spreads over the sea, in varying layers, varying shades; wrapped in this azure are green islands, looking like great patches of bog, black ones, jagged, rearing up out of the ocean like stumps of teeth…’

The coastline is wholly exposed to the fury of the Atlantic, yet it presents a variety of shape and profile, not all blunted into anonymity by the scouring elements. Achill Bay is an archipelago of islands, a vibrating arena of appearance and disappearance, as islands seem to come and go through the rain-soaked atmosphere. The weather varies swiftly and dramatically from brilliant sunshine to squalling rain (‘the rain here is absolute, magnificent and frightening’, wrote Böll), and this became a factor in the artist’s working strategy.

When he first arrived, Elwes made a three-sheet watercolour of the bay, painted in a more naturalistic manner than usual, a direct transcription of his first impressions. The works on paper made during this Irish trip tend to be narrower than his habitual format, partly to make them more portable in extremes of weather: the lashing rain could erase an image entirely, and while Elwes welcomes the action of water on his work, he did not want to lose everything. In Ireland, the day is not complete without rain of some sort and measure.

Elwes’s paintings are built on soft grids and traces, on the ability to recognise the value of what others dismiss as worthless, or never even notice. His imagery is flowing, liquid, echoing the materials from which it is made. (He likes to quote Heraclitus: ‘Everything flows’.) He uses water-based paints flooded on to large sheets of heavy paper, or turps-thinned oil, encouraged to run swiftly across a canvas. He paints beside water, estuary or ocean, and the rhythm of his work is tidal, the ebb and flow of richly improvisatory responses: the layering of colour particles floating or submerged. Here is the flotsam and jetsam of history, in a continual process of statement, erasure and erosion.

The grid has long been a central underlying structure to Elwes’s work, but he has never deserted the ground for the grid. The hidden dynamics of a tree that grows upwards yet spreads across, the traces of post and lintel architecture in so many of his earlier paintings, the vertical stripes (with horizontal crossings) of watery reflections, all these express versions of the axes that exist at 90 degrees to each other. The co-ordinates are there, even if not obviously delineated. At the same time, Elwes remains fascinated by the permeability of things, the state of flux in which we all exist.

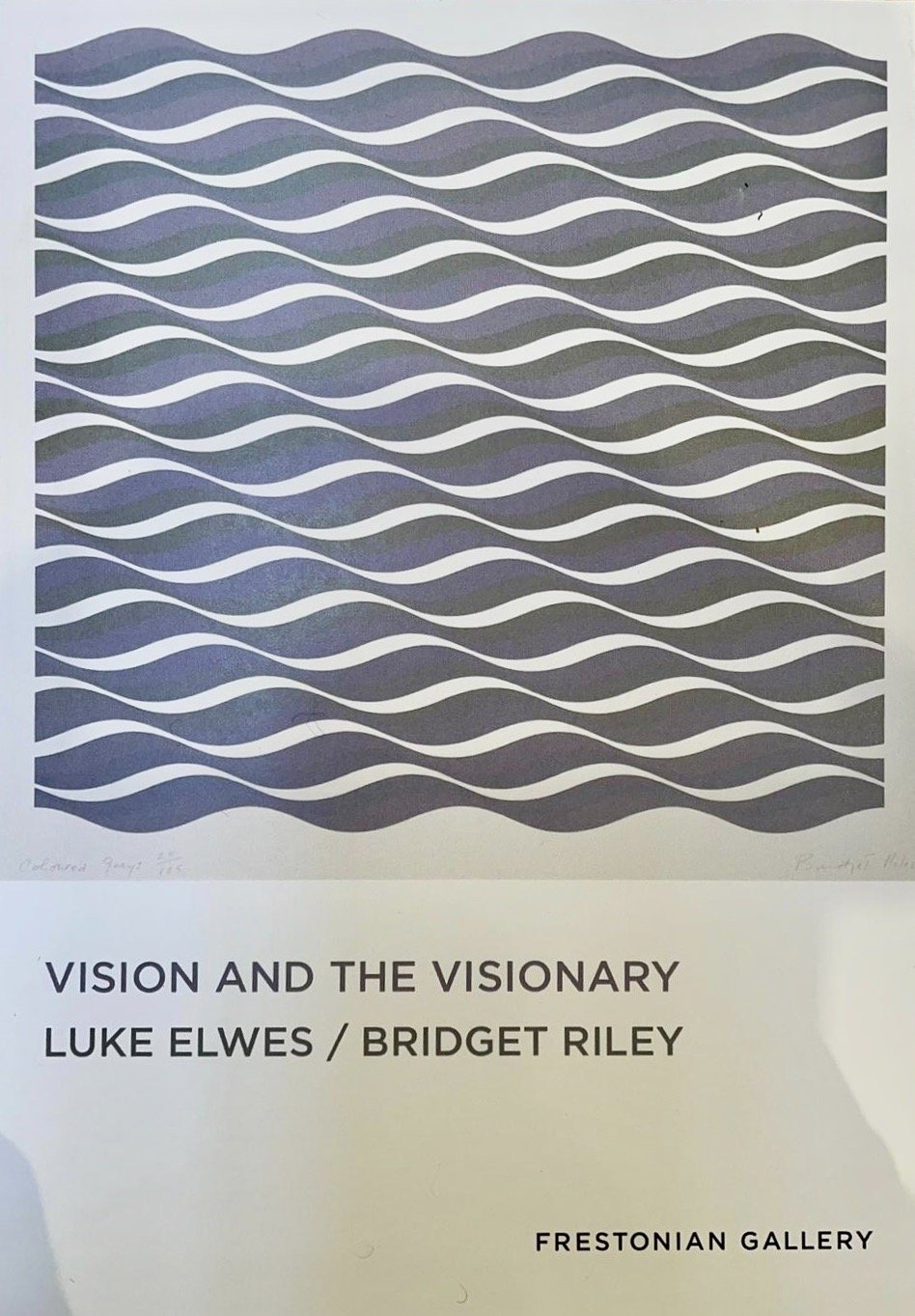

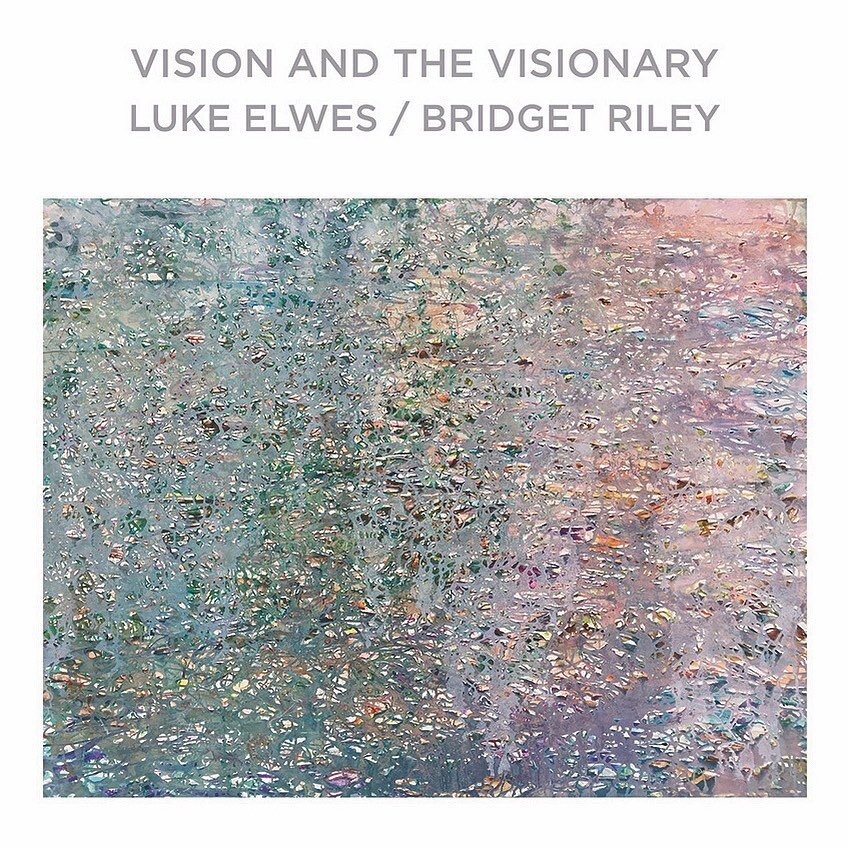

Although Elwes makes good use of rectilinear structures, he recently saw his work in a useful new context. The experience of showing alongside Bridget Riley (at Frestonian Gallery in February 2023) was an informative one, making him aware that his approach was perhaps more formal than he had thought, but also that his grids were a lot more relaxed than Riley’s. Her surfaces with their extreme interplay of space and geometry, their dialogue of verticals, horizontals and diagonals, are much more starkly composed than his. The emphasis in Elwes’s practice on revealing and concealing is closer to the actions of natural forces, and this has been reinforced by the body of work resulting from his Mayo residency. There is a new expansiveness to the imagery, inspired by the comparison of marginal coastal sites (east of England and west of Ireland) and a fruitful intersection and overlap of interests.

These are images with a breadth and spaciousness, a play of visual field, that invite comparison with modern American painters much admired by Elwes: for instance, Jackson Pollock, Mark Tobey, Cy Twombly and Brice Marden. Elwes operates in the borderland between abstraction and figuration, while deriving much of his inspiration from the world around him. Brice Marden spoke tellingly of ‘natural objects turning into, and not quite turning into, abstractions.’ This is the territory that Elwes investigates. Marden also described how drawing is about joining things up, making relationships and ‘at the same time letting the drawing itself do the work… They start out with observation and then automatic reaction, and then back off, so there’s layering of different ways of drawing.’ The layering for Elwes too inheres both in the methods of working and in the content.

These are points of reference only, by which to navigate and consider Elwes’s work. Equally he draws inspiration from Chinese scrolls, with their intense dialogue between near and far. Or the waterfall prints of Hiroshige. Or, again, maps and sea charts and the gridded prayer flags of India and Tibet, all of which endeavour to bring a sense of order to the wild and chaotic. With such exemplars, Elwes has developed a wonderfully loose and flexible calligraphic style, originating in the works on paper, and which he has now begun to explore in his large oil paintings. The oils have gained some of the immediacy and spontaneity of the paper works, employing poured thin pigment to create their structures.

The imagery is as usual built up in layers, with a final application of turps run fast vertically down the canvas, invading and modifying the existing paint marks. This is countered and balanced by the other axis of the grid: paint run equally quickly horizontally across the field of action. The first time he attempted this strategy, Elwes could not entirely predict the results, but he has learnt what might happen and now proceeds with ever greater assurance. The whole of his painting practice is inflected by this potent combination of experience and risk. The process is one of constant obliterating and re-forming, advancing and retreating, as imagery is seen to be drifting in and out of view, and travelling from one place to another. That rhythm, nature’s peristalsis, permeates this new work.

Initially, Elwes thought of titling this group of paintings ‘Drift’, but he realised that they had more to do with ‘constellations’; in his own words, ‘as in a group or cluster of similar things (forms and places), as well as a cluster of circling and returning thoughts and memories’. The notion of ‘constellations’ is borrowed from a series of 23 gouaches made by Joan Miró in 1940-41, through which he refreshed the poetic and calligraphic language of his art. Since they are all to do with the power of the imagination, with transparency, layering and intersecting forms, it’s easy to see why Elwes should be drawn to them.

Here is the distinguished French poet and art critic Jacques Dupin writing about Miró’s Constellations in his 1993 monograph on the artist: ‘Linear invention and rhythmic imagination are realised with miraculous purity. The interpenetration of graphism and chromaticism produces a counterpoint whose precision and spellbinding power irresistibly evoke music.’ Much the same could be said of Elwes’s fluent new paintings: through a radical and resourceful use of layering he by turns conceals and reveals his subject, in a kind of inspired calligraphic archaeology of painting. His researches offer us intriguing new prospects and perspectives loaded with meaning.