VITAL SIGNS 2015

Working on paper

This exhibition is about the activity of mark making and the myriad thoughts and imaginings that surface on paper through this elemental act. Sometimes it is simply a beginning, a way of moving forward into as yet unknown territory - a ‘voyage’ as Andrzej Jackowski describes it. At other times it is a way of working things out, playing with nascent possibilities; the paper becomes a container of private thoughts, a testing ground, a dream site, a mind map. Often it is a volatile and uncertain space, in which intangible ideas are questioned and probed by hand and where the interior realm - what Tony Bevan calls ‘an internal landscape’ - starts to assume some imperfect external form.

If making work on paper, either as a direct impression or by reversing it in print, is intimately linked to the practice of painting for these artists (indeed for Merlin James it functions as a sub-media of painting), it is also an exercise in its own right: a method of revealing, revising or returning by stages to the visual possibilities set in train by those first markings and incisions, as well as by the many which preceded it. The outcome of this process may appear conclusive while also forming the seeds from which future projects can grow. It is both a site of arrival and a site of departure - one in which the act of making is intrinsic to its meaning and where, as Timothy Hyman says, ‘if you’re lucky, everything falls into place’.

All this, and more, is contained in a ‘work on paper’, which as well as allowing the viewer more direct and immediate access to an artist’s concerns, ‘by using the images to gain the conscious experience of seeing as though through the artist’s own eyes’ (John Berger), also reminds us how the piece of paper awaiting our impression will always be there (even in an age mediated by the screen), inviting us, as it has done from earliest childhood, to make that vital mark.

Twelve London artists

Among the twelve artists brought together for this show there are long standing professional and personal links. All of them went to art school in London and most continue to exhibit and work in the city where they began their careers. Lino Mannocci curated a touring show in 2007 entitled ‘Gli Amici Pittori Di Londra’ in Italy that included many of these artists (along with Ken Kiff, R.B. Kitaj, Sandra Fisher and John Davies), and this collaboration continued in 2010 with the exhibition ‘Another Country’ at the Estorick Collection in London.

Although their concerns and approach remain separate and distinct, what is evident in all the work is a shared concern with, and a continual return to, the observed world, as well as an ongoing dialogue with the visual language of the past. If the world ‘is in flux’, both for Timothy Hyman out on the street and for Glenys Johnson in the studio, it is precisely what she describes as those ‘layers searching for a story’ which Alex Lowery identifies as needing ‘translation’ through ‘bringing the artist’s materials imaginatively to bear on it’.

Together they stand in a tradition, engaging in an ongoing dialogue as well as a tacit collaboration with it through shared techniques and mediums. The simplicity of the acid bite is for Merlin James another way of exploring the complex play of historical genres on the form and function of the painted image. In his woodcuts Arturo Di Stefano uses the simple device of reversal not as a setback (or a reversal in time) but as a ‘throwing into relief’ that brings a living image into present time; while Lino Mannocci explores a range of monotype techniques to superimpose one kind of history on another, pressing a range of classical motifs that serve as private symbolic markers onto rubbed vellum surfaces already freighted with their own past lives and secret meanings.

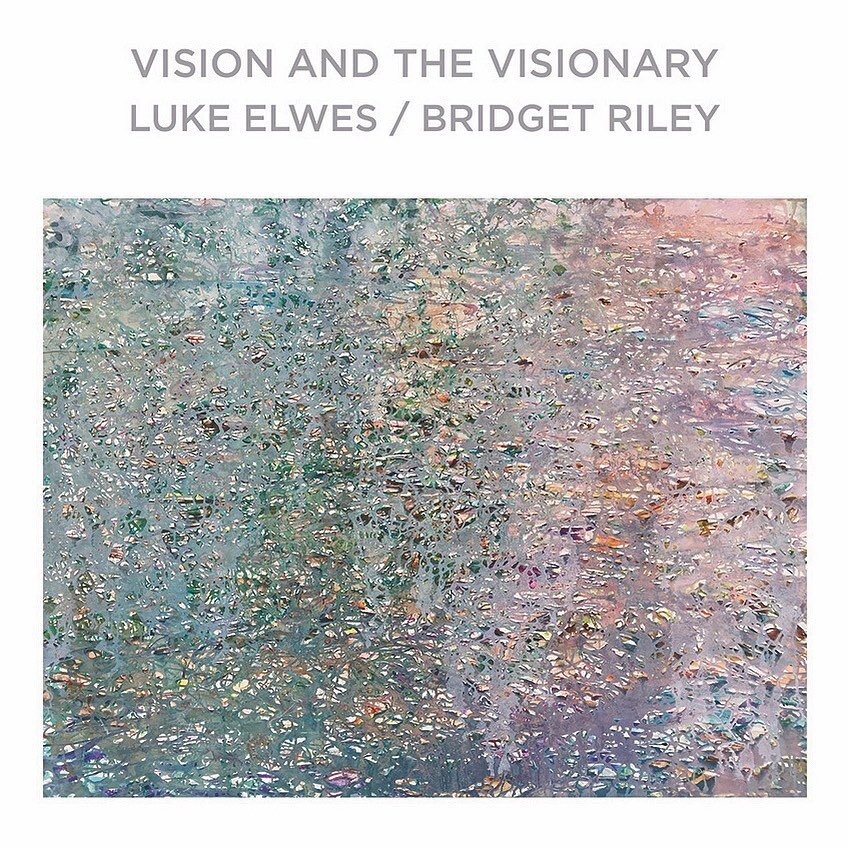

Beneath this haptic process lies the paper, its ‘ground whiteness’, as Glenys Johnson describes it, generating both desire and apprehension. For some of the artists here the surface luminosity is integral to the work: in the veiled washes of Christopher Le Brun’s richly saturated colour fields and the untouched areas of paper that re-emerge from the patinated surfaces of Luke Elwes’ water stained images. Charlotte Verity’s sepia and grey tinted washes, in which ‘petals hold light like snow’, glow with a brightness that similarly suffuses Thomas Newbolt’s transient figures in his watercolour studies, while Arturo Di Stefano’s darkly inked woodcut interiors are punctuated with passages of pulsing yellow light.

For others, something is revealed and remembered as, in Jackowski’s words, the space is ‘carved out of darkness’, or pulled from the unconscious; or else is constructed from dark materials (within Bevan’s dense web of charcoal), just as in Mannocci’s palimpsests the material history of the surface forms the substrate from which new images arise. Through these acts of retrieval a liminal or inner space is delineated. It might be located in private interiors - Jackowski’s rooms, Bevan’s studio, Di Stefano’s atelier – or on the borders of interior and exterior worlds, where Verity’s petal and leaf shapes hover. Elsewhere, it is external places that are symbolically encoded or transmuted into metaphors. Hyman’s ‘London’ and Lowery’s ‘West Bay’ are territories both familiar and strange, while the elemental spaces of Le Brun’s desert and Elwes’ river indicate a noumenal realm hidden within the temporal flow of phenomena.

The work on paper is a site of memory and action. It is a direct transcription, bearing the signature - the touch, the pressure - of the hand that made it, and while necessarily contingent and unpredictable, it aims essentially at ‘the transfer of one person’s experience to another’. In this sense it is not what Merlin James describes as ‘post medium’: images are not generated in an untouchable and depthless space - digitally encoded and filtered through a screen - but remain resolutely in the realm of matter and touch, compounded of the earthy and magical.

Luke Elwes London 2015